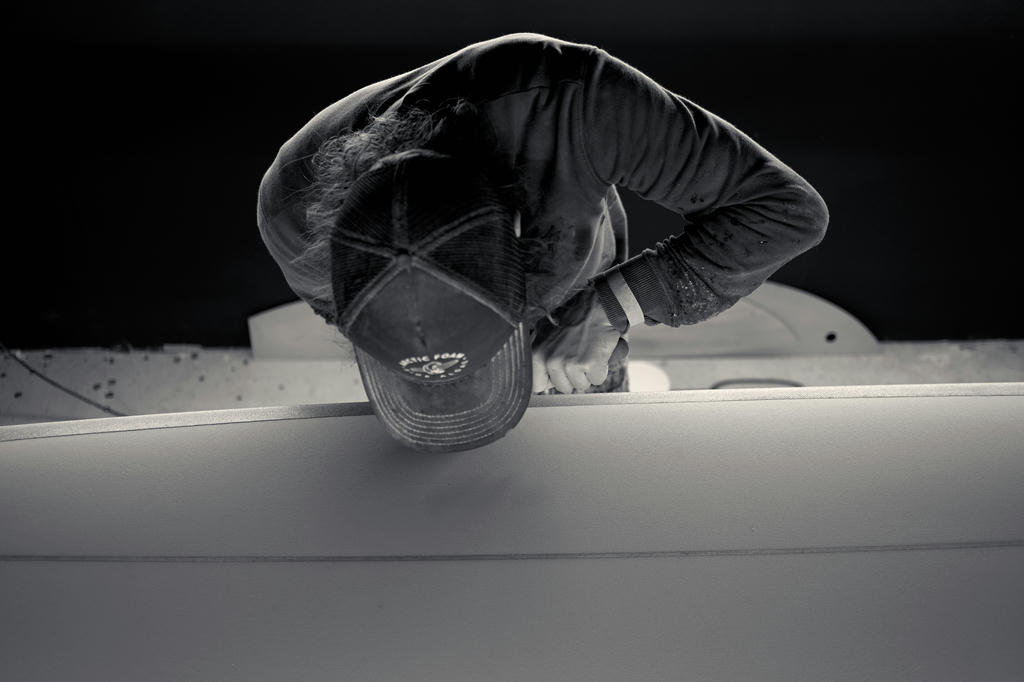

Ollie Cooper

Hang around a factory, wait for someone to call in sick and offer to help out — that's how you become a surfboard shaper. At least that's how Ollie Cooper got started at OPEN here in Cornwall.

Surfing is synonymous with Cornwall. It’s hard to escape — literally — the hoards of British tourists that arrive come Spring, brightly coloured boards strapped to the roof. Surfing has exploded in popularity in recent years, with lots of people buying cheaper, mass produced boards for their occasional trip to the beach.

For the seasoned surfer — one that will endure the cold and wind to catch a winter swell — a hand made board is something special that deserves respect, bordering on reverence. For those people, a trip to OPEN on the cliff tops above Trevaunance Cove is a treat. Not only are there hand shaped boards to rent or buy, designs from the world’s best shapers but also the chance to shape your own under the guidance of OPEN’s head of production: Ollie Cooper.

Ollie has been almost single handedly responsible for every board that has come out of OPEN in the past year. Whether it’s one of OPEN’s much beloved Eggs, a custom Beau Young or one of his own designs; Ollie was probably pivotal in it’s creation. He’s a quiet, humble person but his enthusiasm and love of surfboard shaping is infectious. I spent a day watching him work, chatting about boards, surfing and life at large and he almost had me convinced I should put down the camera and pick up some sand paper!

OC — Ollie Cooper / JD — Jamie Dumont

JD: So, when did you start shaping? We talked about your time at LOST in New Zealand, but how much had you done before?

OC: I’d done a bit, but not on a commercial scale. I think I shaped my first board late 2011 on a similar course to the one we offer here at OPEN, but with Luke Young in Plymouth. It was part of my uni course which was great. From there I ended up going back home, so tried to get some practice shaping boards in my garage and back garden — the classic DIY approach — but quickly realised it costs you ten times more to make those mistakes by yourself. So, I thought “I want to get a job in an actual factory”, and learn from what might be hundreds of years of collective experience in some factories. I wanted to learn how to do it all properly. When I moved down to Cornwall I managed to get a job with these guys [OPEN], helping out with ding repairs, sanding and doing a bit on my own. Slowly I started picking up more work, and didn’t mind working for free because I’m learning at the same time. I ended up spraying some of Gary McNiell’s boards and fixing fins here. Whilst traveling I worked for LOST and came back here after.

JD: And what year were you in New Zealand?

OC: Ah, I can’t remember now! I came back in 2018 maybe?

JD: So quite a long time between when you first started and your time at LOST?

OC: Yeah, absolutely. In that time I felt I was quite confident at glassing, but the guys at LOST just tore me apart and rebuilt me from the bottom, which was quite cool.

JD: I remember you saying it was a really steep learning curve. How did that come about?

OC: LOST was just a really lucky bit of timing. I was in New Zealand traveling and the day I ran out of money and realised I needed to pick up some work, the job popped up on one of the groups I followed. It was just like “Oh, OK, I’ll apply and see what happens” not even expecting to get it; but Tommy [Dalton] was just like “When can you come in?”. It was a six hour drive so I just said “Tomorrow!” — It worked out really well.

JD: So how long did you work for them?

OC: Maybe six months? Not long, but we were making 12-14 boards a week so I racked up a couple of hundred boards whilst there. It’s a pretty crazy pace, but it’s a really nice setup where you have one guy that does sprays, one guy does dings, one guy does sanding, one guy does shaping, one guy does glassing so between us it was really easy. Anyone could step into the other roles if they needed to, but we had our specialities that we could get really good at.

JD: And was that glassing for you?

OC: Yeah. Always glassing for me.

JD: They got you to glass some super lightweight boards didn’t they?

OC: Yeah, so we worked with Maz Quinn and a lot of the other pros around Gisborne. We were making ultra light, single 4oz top and bottoms and just trying to build those boards as well as you can with the limited materials. Just trying to make them last longer than a single surf.

JD: We talked about how you use the techniques you learnt to make “regular weight” boards stronger. Is that something you’ve continued to do?

OC: Yeah. Building for pros, you’re doing the extra stages to try and make them survive a session, whereas here we’re glassing them at a regular weight but with those extra steps it’s the same weight as your regular shop-bought board but it’s going to last so much longer. That’s something I really care about, just making boards last. I’m sick of seeing boards that fall apart after six months under the feet of normal guys, not even pros. It just makes sense to me.

JD: How do materials play a part in the end result, or is it largely your knowledge that’s the difference between a board that lasts six months and one that lasts for years?

OC: I guess it’s a bit of both. There’s certain brands of fibreglass I prefer using, and some that feel stronger. Even if it just sits flatter whilst you’re glassing you get a better finish that’s easier and quicker too, but also making it stronger. We use an extra layer of s-glass on the deck of every board here which was originally built for the aerospace industry. It’s a much tighter weave at the same weight and is about 20-30% stronger. I’ve noticed on my own boards that I don’t get pressure dents in the first few months. They eventually happen but not right away.

JD: I have a friend that rides a kevlar board and it feels solid and totally different. What’s that about?

OC: You don’t really get much flex with kevlar or carbon. There’s something to be said for a bit of flex in a board. It gives you that feedback which is enjoyable. Surfboard construction has been improving for the last 30, 40, 50 years; making the board really strong but also feeling the same as they always have. If you as a surfer have to put six months or more into getting used to the new feeling then it’s just going to hold you back. It’s interesting, some of the new kids coming up learnt on epoxy and EPS and it’s becoming a bit more mainstream because they’re totally happy on them.

JD: I know it varies, but how long does each of your boards take to make?

OC: I reckon it’s 12-15 hours of working time depending on the length, finish and also whether you’re starting with a machine shape. Most of my own are hand shaped though. I think what most people misunderstand is that building a board is lots of short processes with drying time in between. Most boards actually take about two weeks on glassing alone, just to make sure everything cures properly and is perfect at every stage.

JD: It’s easy to say “12 hours” and have someone think “2 days with huge lunch breaks”.

OC: That’s exactly what I worry about! I don’t like saying “12 hours” and then 2 days later someone asks “why isn’t my board done?!?”.

JD: You said that in your opinion shapers need to understand both hand and machine shaping, so that even if they have a preference they appreciate the other?

OC: Yeah, absolutely. There’s space for both. I understand the arguments that are made for and against each approach but it’s two completely different business models. Any one person should be able to do both; there’s skills involved in either side.

I appreciate if someone can take just a saw and planer and make a beautiful board, but if they have a year-long waiting list it’s going to put people off. If they can’t sit at a computer and translate their hand shapes to the software, it’s only really holding their business back.

At the end of the day every board here is hand finished, and glassing and sanding can change the end result a lot. All the important stuff like the rails and the concave which need tuning is done by hand still. It’s perfectly possible to make a good machine cut into a bad board. Even an experienced shaper could take another shapers machine-cut board a totally different direction in the hand finish.

JD: At OPEN you get guest shapers coming in. What’s it like to work with them?

OC: Oh, absolutely epic! It’s one of the reasons why I wanted to work here. I love gaining experience from other guys in the industry that made me want to do this in the first place. You get people here who would never normally shape in the UK and suddenly you’re working alongside them for one month, two months or in Beau [Young]’s case like five months!

JD: I was surprised how long they stay. It’s not they’re here for a week, shape a dozen boards and they’re off again.

OC: It’s more than work. You come here, you hang out, have a good time and all learn something from each other. It’s such a good experience to see what they’re doing and learn every step of the way.

JD: So it’s not just a one-way thing? You’re learning from each other?

OC: I would never to pretend to be able to teach some guys anything because they’ve been doing it so long and are so good at what they do, like Neil [Purchase] for example. He’s a machine! I worked quite closely with Beau when he was here, and we’d discuss design theories and draw out new fin templates, tweaking tiny details. It’s a nice collaborative process. Other factories do shaping runs where shapers only stay a few days and bang out as many boards as possible and then leave, but there’s no back-and-forth.

JD: Even with these guest shapers, you’re the one that does all the glassing?

OC: In most cases, yeah. For the past year or so I’ve been the only glasser here. Everyone likes things slightly different though. Neil has done some glassing in his time so has things he wants to see, and I think Josh Keogh is the same.

JD: I know you had a heavy summer last year with a big backlog and a shortage of blanks.

OC: Haha, yeah I’m not sure I saw daylight last year! The whole industry has exploded which is amazing but it’s hard to keep up with. We’ve started training some new people now who all have attention to detail and patience which is the main thing for me. You can’t teach those things. I can teach them how to sand, fix fins and glass. We’re slowly building towards a more comfortable schedule.

JD: So it’s the attitude and personality you look for? Everything else can be taught.

OC: Yeah, completely. The way I see it is that if I spend an extra hour on a board either in the evening when everyone else has gone home or missing out on a surf, it might mean that board could last five, ten maybe even twenty years with the way we build them. A lot of the locals here are riding our boards and we’ll see them in the water regularly, and I don’t think anything would break my heart more than seeing those boards covered with dings and dents six months later. I want to see those boards for years to come!

JD: Whilst I was here you were teaching a couple of apprentices. Is mentoring — passing on skills — something you want to do more?

OC: I’m always up for making my life easier! It’s one of those things… Historically, it’s been hard to get into the surfboard industry. Nobody wants to teach you from scratch, so you have to go and teach yourself in your garage and make the expensive, frustrating mistakes.

Trying to create a larger talent pool to choose from helps us because if we turn people away, they go make their mistakes but eventually become a competitor, which doesn’t help anyone. We need more people helping us and they need someone to teach them. There’s something to be said for building a factory where you’ve got a sick team of people all listening and learning from each other.

JD: So if someone is reading this and thinking they want to do what you do, you’d tell them to find their nearest factory and start offering to help out?

OC: Absolutely! Some factories will say “we don’t have the time!” because the industry is growing so much at the moment, but if you stick with it they will eventually come round to helping you. Turn up, hang out, maybe showing up with some beers — which is the classic way to earn some favours — pick up a broom and ask if you can help cleaning out the bays, or just watch if they are cool with that. In the long run that will pay off for everyone.

JD: Changing the subject, now that we can all travel again have you got a few surf trips planned?

OC: I’m trying to get back to Bali this year, it’s my thirtieth birthday in July and I’ve got a couple of weeks booked off work, which I’m really excited for. Other than that I’d really enjoy a trip to Portugal or northern Spain where there’s some amazing waves. My last trip was to Fiji and decided on my last day there that I need to find a way to make surf trips a regular thing.

JD: It’s a tough balance between making boards for other people and surfing them yourself. How do you find that balance and not get burnt out?

OC: Yeah, keeping that right is really important to me. If the waves are good then I’ll get out and surf or find something new to appreciate in the area; Cornwall is sick. Sometimes it’ll need to be something with absolutely no relation to surfing, because when you’re surfing your own boards you’re still in “work mode”.

I had a chat yesterday with an old friend who also shapes, and we were both complimenting each others boards but then critiquing the tiny details on our own. It’s great getting to work it out in the water but hard to disengage.

I also like go climbing or get away somewhere like the Peak District that’s completely outside my normal bubble.

JD: Is there one board that you’re riding more at the moment?

OC: I’ve just finished a new version of the fish that I’ve loved for like the last four years. Made a few changes to help it go well in smaller waves with a tighter turning radius which I really like, but still has that twin-fin straight up acceleration.

JD: Are there any boards that you’ve had ideas for and want to make, but haven’t gotten round to yet?

OC: It’s been hard having been so busy lately, but I want to shape something that’s kind of verging on a performance shortboard. After my time at LOST, that inspired me to go a little more that way. When boards get that small and refined, there’s very little margin for error and it’s a good challenge.

JD: That’s brilliant, thanks Ollie!